Cruising the Museum: Animating Queer Sexual Geographies & Histories

We invited local artists and writers to interact with and reflect on our Community Arts Space projects. Here, Christopher Smith writes about the Transformative Justice Project: Intimate Encounters ~ Animate Histories, presented in partnership with Salon Noir, The 519, and YYZ Artists’ Outlet.

Histories of queer sexual life, more specifically ‘cruising,’ often reside in the personal realm as shared oral histories among friends that gesture toward the desire for sexual intimacy in unlikely places: the alley, the park, the backroom, the bathhouse. Histories of cruising—the search for and engagement in sex in ‘public’ or ‘semi-public’ spaces—occupy a particular kind of archive precisely because they are stories that offer an anonymous map of queer desires and intimacies.

This summer, the Gardiner Museum, in partnership with Salon Noir, The 519, and YYZ Artists’ Outlet, presents Intimate Encounters ~ Animate Histories, a Community Arts Space project led by artist Abdi Osman and curator Ellyn Walker inspired by the latent cruising histories of Queen’s Park.

While the practice of cruising is often associated with the sexual lives of gay men (or MSM—men who have sex with men), it would be inaccurate to presume that the lure of public sex has not drawn the curiosity of heterosexual individuals. At the tail end of what has been dubbed the sexual revolution, early 1980s cinema explored themes of cruising with films like Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill (I dig that they are trying to hook up in a museum of all places) and William Friedkin’s Cruising, both of which represented public sex as not only inherently risky, but deadly.

Still from Dressed to Kill (dir. Brian De Palma, 1980)

Intimate Encounters ~ Animate Histories kicked off with two public events earlier this summer. On July 4, Osman and Walker led participants on a tour of Philosopher’s Walk and Queen’s Park, two sites known to many as spaces where one might seek out the companionship of another—usually in the wee hours. This is of course pre-Grindr and the arrival of other hook-up apps. While offering a history of these geographies, Osman and Walker also invited us to consider the landscape and how it has shifted over time. Taking into account the history of persecution and surveillance of queer sexualities by Toronto police, we learned how Philosopher’s Walk, once lush with greenery, would gradually be cropped and tailored to enable the gaze of those unfamiliar with the secret and sacred codes of cruising.

Outdoor Walking Tour: Cruising Histories of Queen’s Park, July 4, 2019

Perhaps one of the most profound aspects of this experience was the invitation to participants to share their individual knowledge of cruising and histories of surveillance. More splendid was the diverse range of perspectives from queer men and women from all walks of life and eras. What resonated most were probably the histories offered by those we would refer to as our elders, which enabled an intergenerational dialogue on the politics of sex, desire, and the policing of public space. While I hadn’t known of Philosopher’s Walk until quite recently, I was nudged to share my experiences of Queen’s Park. I suppose I will say I am elder-ish—though I jokingly prefer grown and well-seasoned—and was inspired to recall memories, like that of my first kisses as a ‘baby gay’ in Queen’s Park during the 1990s. My first dates would usually end with a moonlit stroll through Queen’s Park in search of a lush tree or picnic bench, in hopes of stealing one last moment before my commute back to my mother’s home in the east end.

Spilling tea at the end of Philosopher’s Walk

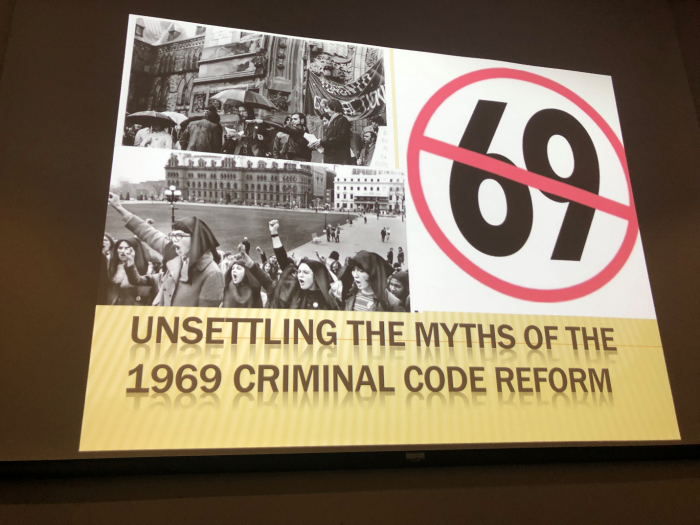

What moved me was that the tapestry of stories offered by participants captured how the lure of cruising, for some gay men, is its radical potential for what writer Samuel Delany has referred to as the ‘democratization’ of queer sex spaces. Cruising facilitates the possibility of intimate encounters across racial and class lines when not everyone can simply “go rent a room.” Adjacent to this is a rich history of queer nightlife, when many of the hottest spots had their home on Yonge Street. This is a history familiar to me, and is conjured and evoked with a deeper understanding because these stories come from a place outside of an official history but rather, from the ephemeral evidence of desire and experience. The public lecture by historian and activist Gary Kinsman on July 18, which delved into the ‘decriminalization’ of homosexuality in 1969, was a welcome compliment in this regard.

Unsettling The Myths of The 1969 Criminal Code Reform, Public Lecture by Gary Kinsman on July 18, 2019.

Speaking to a full audience at the Gardiner Museum, Kinsman offered a thorough examination of local and national histories of gay liberation movements. Not limiting themselves to a history of gay liberation movements in Canada, Kinsman emphasized a history of solidarities between various radical social movements and initiatives in 1969 (Feminist pro-choice groups, as seen in the ‘Abortion Caravan;’ Black Power movements; anti-racist coalitions; and Indigenous sovereignty) that sought not only to have particular laws removed, but demanded substantive changes to the manner in which laws were applied by police and the criminal justice system.

Addressing the mythology of the 1969 Criminal Code Reform, often associated with Prime Minister Elliot Trudeau, as a historic moment in Canada’s journey towards full equality for its LGBTQ citizens, we learned that this is far from the case and much more nuanced. While Pierre Trudeau’s often-cited quote, “There’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation,” may sound ‘progressive,’ a historical amnesia (intentional or not) refuses to reflect on the statement in its entirety. Proceeding the quote, Trudeau stated: “when it becomes public, it becomes a different matter.”

What is meant by ‘public’ in this regard? As Kinsman clarified, queer sexual practices often confound the easy dichotomy of public/private space. Queer intimacies nurtured through cruising often reside in a site that makes such distinctions nearly impossible to grasp. As such, it is not difficult to surmise that the Criminal Code is more often than not applied in a discriminatory manner against queers, poor people, and people of colour at all levels of law enforcement.

The history of cruising as noted by Kinsman, and the living-walking archive cultivated by Osman and Walker tell us a different story. While specific to the conduct of the Toronto Police Services (TPS), a history of the misapplication of ‘the rule of law’ is exemplified by the bathhouse raids in 1981, the raids of sex-related establishments such as the porn theatre The Bijou in 1999, and the raid on the Pussy Palace, a women’s bathhouse during that same era. But we need not reflect solely on history, given contemporary examples such as Project Marie. A 2016 TPS sting operation that initiated the targeted surveillance and arrest of men seeking public sex in Marie Curtis Park, Project Marie reminds us of the pernicious manner in which queer sexualities are surveilled, and how geographies of intimacy and desire are continually redrawn.

These historical indexes, held in my memory, remind me of a moment I was almost ‘found-in,’ a term that was used by police to designate one who was ‘seen’ yet not apprehended engaging in what officers might determine as ‘obscene or illicit behavior.’ During the summer of 1999, as TPS intensified their raids on the Bijou (I think it’s now a photocopy place—smh), I remember my hubris in thinking that “we own the night.”

The red lights began to flash, and the dark room, once fully lit, revealed all kinds of truths that were NOT intended to be made visible. I know the code—it means “get out!!” Many were inclined to run, seek the emergency exit for immediate escape. As a young black gay man, I opted for walking quickly but still dignified in stature. A white gay gentleman took my hand and said, “Sit with me, I know how this works—I have been here before,” and I left unscathed.

Through Intimate Encounters ~ Animate Histories, Osman and Walker have prompted me to seek different geographical clues and registers. “I have been here before,” the gentleman said that night at the Bijou. What is this ‘here,’ I questioned—is it a time, a space, or a wisdom that suggests that queer sexual geographies are continually redrawn, some baring historical traces of desire, but that they will not cease to exist. “We own the night!”

On the cusp of Osman and Walker’s exhibition, I am longing for echoes or hints, a spatial wink that provides a texture to the complex histories of cruising that are offered through the oral narratives provided by participants for this ground-breaking project. I am certain a new map can be redrawn.

Christopher Smith is a Ph.D. candidate in the Dept. of Social Justice Education at OISE/ University of Toronto. His research interests reside in the productive interstices of the fields of Black Diaspora Cultural Studies, Queer and Feminist Theory, including Post-Colonial and Decolonial study. They are currently teaching a course on feminist criminology in the Women’s & Gender Studies Program, in the Dept. of Historical & Cultural Studies (University of Toronto, Scarborough).