Real or fake? How to spot authentic Chinese blue-and-white porcelain

One of the most ubiquitous kinds of ceramics, blue-and-white porcelain took the global markets by storm in the 14th century when potters in Jingdezhen, China’s porcelain capital, began mass producing pottery for export.

The fervor for Chinese blue-and-white porcelain was felt across the world—prompting the development of the British fine ceramics industry, and even inspiring potters in the Middle East, who integrated classic Chinese motifs including dragons, cranes, and lotus flowers into their ceramics.

Besides inspiring many porcelain traditions, the popularity of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain has also spurred the creation of many fakes and forgeries, which frequently appear in art markets around the world. To learn more about how to spot an authentic blue-and-white ware, we asked Dr. Maris Gillette, Professor of Social Anthropology, School of Global Studies at the University of Gothenburg and author of China’s Porcelain Capital: The Rise, Fall and Reinvention of Ceramics in Jingdezhen, for tips on distinguishing real antique Chinese porcelain from forgeries:

Specialize.

There are so many ware types, kilns, and periods that it is almost impossible to be an expert in all of them. By contrast, if you have a narrow focus, you really can build expertise that will help you avoid fakes.

Handle as much of the real thing (within your area of specialization, if possible) as you can.

The more ceramics you see and handle, the better your intuition is about the wares you focus on. You get a sense for the kinds of flaws that characterize your period and the spectrum of possibility for genuine wares.

Work with a reputable dealer.

A good reputable dealer will have handled a lot of the ware that you are collecting, and will also be able to give you information about provenance and perhaps even provenience. Solid documentation about provenance is your best protection against buying a fake.

Learn about the potting and firing techniques for the ware that you are interested in.

For example, if someone tries to sell you a piece of blue-and-white or polychrome ware from Jingdezhen with a sandy or gritty bottom, it is a fake (e.g., it is Swatow ware, influenced by Jingdezhen, but not made in Jingdezhen). In Jingdezhen, ceramics were always fired in saggars (kiln boxes). Similar issues apply for potting. For example, during the Yuan dynasty, many potters used press-moulding techniques, particularly for larger wares, rather than wheel-throwing techniques. In later periods, such as the Qing and the 20th century, potters could throw very large wares on wheels.

Learn about what gets faked, today and in the past.

When contemporary potters in Jingdezhen started making counterfeits, they began with Ming and Qing blue-and-white wares, because it was very easy to find shards of these wares in Jingdezhen and to get access to real pieces to copy, not in the least through the Jingdezhen ceramics museum. By contrast, exportware was not a focus—although, as prices rise for export ware on the art market, this has become a more attractive ware to copy. It is very helpful to keep track of prices at the major international auctions—this is what potters who make fakes do! People produce fakes (and works that are sold as antique replicas) to make money, so of course they want to know which wares are most valuable on the art market.

For further reading…

A great source for learning about potting and firing techniques is Ceramic Technology, Science and Civilization in China 5(12), a monumental book by Rose Kerr and Nigel Wood. This is the single-most comprehensive source on Chinese ceramics that has been written to date.

Dr. Maris Gillette will be speaking about the wide-reaching influence of Jingdezhen blue-and-white porcelain at our upcoming Gardiner Signature Lecture. Learn more and get tickets here.

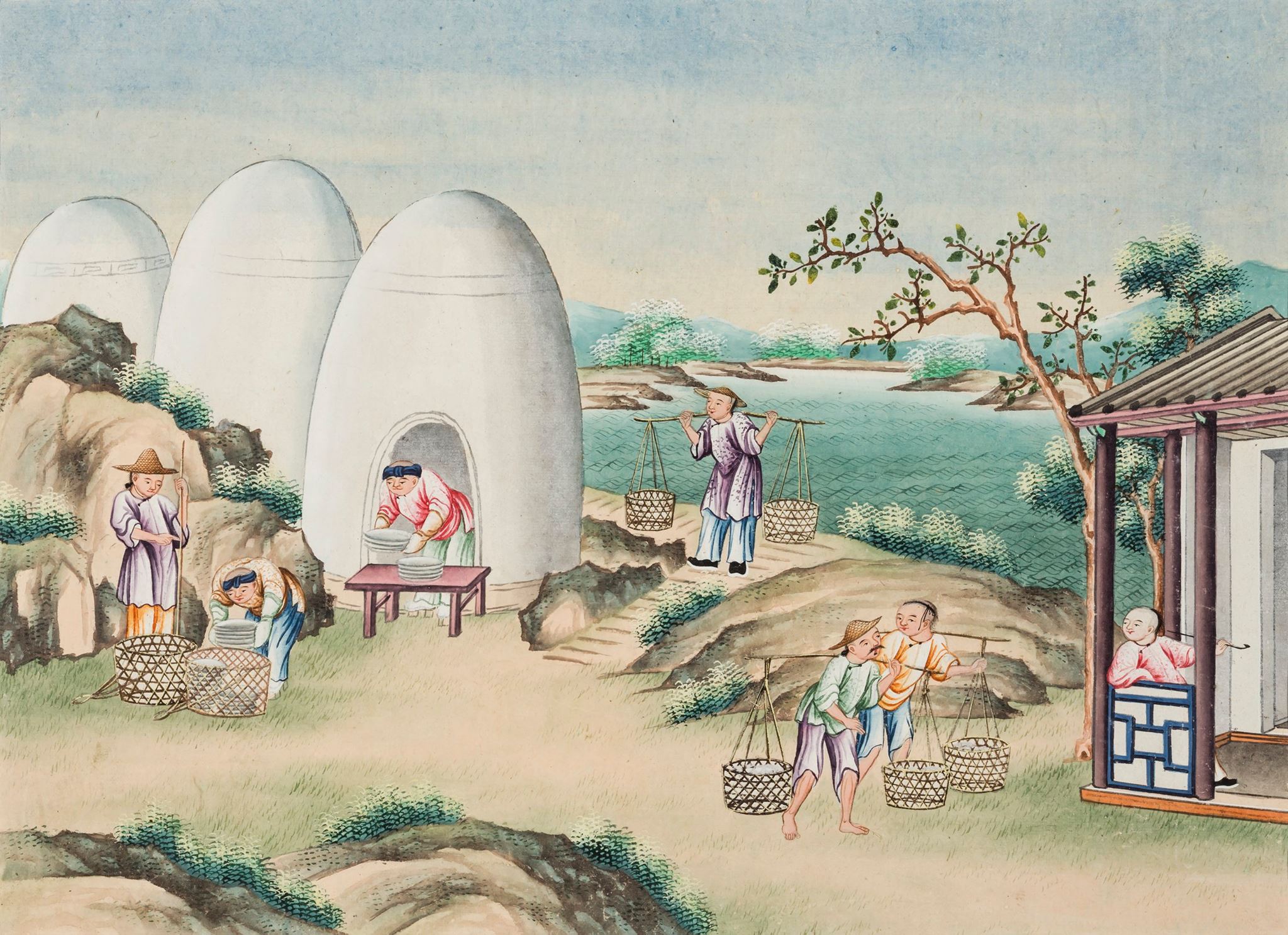

Images: [1] Ai Weiwei, Blue and White Moonflask, 1996. Courtesy of a private collection, USA [2] A selection of blue-and-white ware currently on view in our Sharp

Gallery [3] The process of porcelain production. Guangzhou, China, c. 1810. Gift of Lindy Barrow, G13.2.1-12 [4] ‘Bianhu’ (flask) with bajixiang or the eight Buddhist emblem, c.1736-95, China, Jiangxi, Jingdezhen, Porcelain, underglaze cobalt blue, The Robert Murray Bell and Ann Walker Bell Collection of Blue and White Chinese Porcelain