Tulipieres, asparagus dishes, and chamber pots: The histories of bygone household objects

By Rong Zou, Operations Associate

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has disrupted almost every aspect of daily life for millions of people around the world. We’re all urged to spend more time at home and practice safe physical distancing. Most services are operating at reduced capacities and hours, while others remain closed. We’re constantly evaluating the risk of various activities and behaviours and asking ourselves the question: What is essential and what is not?

This moment of temporary retreat into the private sphere offers us the chance to think about the relationship between the inside and the outside worlds, and the things we consider central to our ways of life. Ceramics from the past highlight the social function of domestic objects and exemplify the ways in which they contribute to identity. While some may seem strange or marginal to us, they were crucially important elements of the household at different moments and in different parts of the world, and can tell us a lot about the time periods and places from which they came.

These bygone household objects from the Gardiner’s collection of European porcelain shed light on specific historical customs, discoveries, and events.

Tulipiere or Bulb Bowl

Flower Container with Multiple Sockets, London, England, c.1690-1705, Tin-glazed earthenware (delftware), Gift of George and Helen Gardiner, G83.1.529

Did you know that the tulip is a close relative of the onion? When tulip bulbs first arrived in Antwerp from Constantinople in 1562, they were thought to be onions and were roasted over the fire and served with oil and vinegar. The first blooms appeared more than 30 years later at the botanical garden at Leiden, inspiring what is now known as Tulip Mania. Tulips became a coveted luxury item and status symbol.

This delftware tulipiere, or bulb bowl, was manufactured in London, England c. 1690-1705. It was used to grow tulips, crocuses, or hyacinths indoors. A bulb would be placed in each of the eight tubular ‘spouts’, which have access to a shared water reservoir. While they have since fallen out of fashion, tulipieres were commonly found in the houses of European elites. Large ornate versions reflected the owner’s wealth and position.

Watch Curator Karine Tsoumis talk more about the Dutch tulip trade

More recently, the tulipiere has become a catalyst for the creation of new objects by contemporary artist like Thomas Aitken and Kate Hyde, Gaetano di Gregorio, and Ronald van der Hilst.

From left: “All the World’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players” by Thomas Aitken and Kate Hyde; Tulipiere Dark Vase by Gaetano di Gregorio; Vase Isphahan by Ronald van der Hilst

“WASTE NOT WANT NOT” Charger

“WASTE NOT WANT NOT” Charger, England, Minton, c.1849-1855, Stoneware with encaustic decoration in coloured slips, Gift of N. Robert Cumming, G96.3.20

This bread plate designed by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852) in the Gothic style is inscribed with the motto “WASTE NOT WANT NOT.” Pugin, an architect and designer, advocated for a return to medieval faith and social structures, and believed that the moral intentions of an object could be transferred to its user. This plate was manufactured by Minton in England c. 1849-1855 using the medieval encaustic process. This “inlay” technique revived by the manufactory involves filling a stamped or recessed design with a contrasting colored clay or slip. The design of this charger is listed in the Minton pattern book as number 430.

The motto references the economic and agricultural failures of the period known as the “Hungry Forties”, when political unrest and poor harvests were widespread across Europe. It exemplifies the essence of the Gothic Revival style, which sought uniformity between function and aesthetic, and to support moral uplift during a time of religious and economic upheaval.

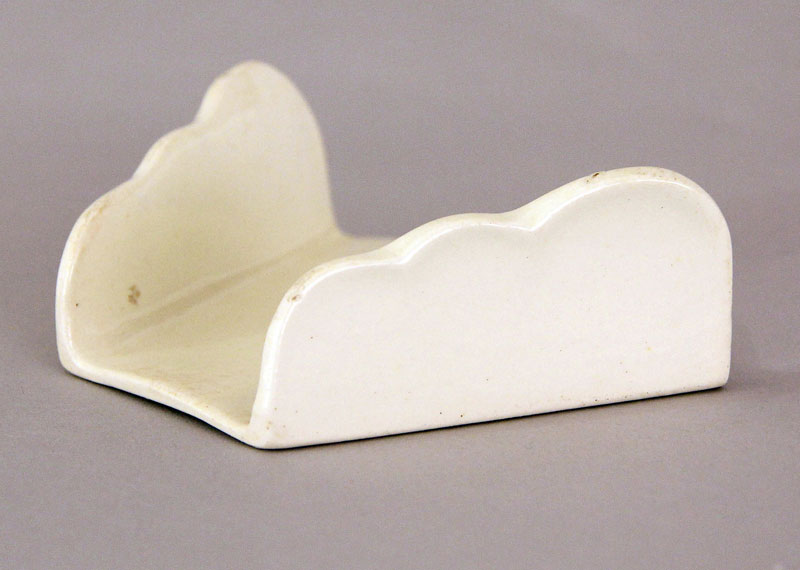

Asparagus Dish

Asparagus dish, England, c.1790, Glazed earthenware, Gift of Jean & Kenneth Laundy, G08.2.49

While asparagus traditionally has a short growing season that lasts from April to June, King Louis XIV of France had such a fondness for it that he enlisted his head gardener, La Quintinie, to cultivate it all year round. La Quintinie devised a way of growing asparagus in hotbeds, a technique that was adopted throughout Europe. The desirability of asparagus led to the development of dedicated utensils for serving it.

This creamware asparagus dish c.1790 was most likely made in Yorkshire, England. Wedge-shaped servers like this one were used to hold a small bunch of asparagus with the stems facing outward. When several of these wedges were arranged together, a circle of asparagus would form to please the eye.

Ewer and Basin

Ewer and Basin (Broc à feuille d’eau et jatte), France, Sèvres, Decoration attributed to Antoine-Toussaint Cornailles, 1758, Soft-paste porcelain with overglaze enamels, gilding, Gift of George and Helen Gardiner, G84.1.2.1-2

Before cutlery became a common fixture of the dining table, the ewer and basin were used for handwashing before and after meals. This Sèvres ewer and basin epitomizes the refinement and opulence of 18th-century Rococo decorative art. It was probably kept in a bed chamber or boudoir, and used to rinse one’s fingers following a light morning meal. The delicate gilding creates a bold visual impact and speaks to the exclusivity of Sèvres, which enjoyed a monopoly on the use of gold until the French Revolution.

The sensational pink ground was a new creation of the artist Philippe Xhrouet in 1757. It was initially sold in December 1758 and became associated with Madame Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV, who was particularly enamored by it. The color was discontinued after her death in 1764 and subsequently referred to as Rose Pompadour.

Chamber Pot or Bourdaloue

Bourdaloue (Lady’s Chamber-Pot), France, Chantilly, c.1745, Soft-paste porcelain with tin-opacified lead glaze, overglaze enamels, The Hans Syz Collection, G96.5.84

The chamber pot was not merely stored under the bed; it traveled often, accompanying a lady to the drawing room or out in public. When nature called, she would find a quiet corner and slip the pot underneath her heavy garment and relieve herself. Her maid would then discreetly empty the pot, presumably out a window, with a polite cry of “Gardez l’eau!” which translates to “Watch out for the water”. The common British term “loo” may derive from the anglicized version of this warning.

This chamber pot, called a bourdaloue, was made at Chantilly c.1745. One amusing, though unlikely story, is that it was named after a Jesuit priest in the court of Louis XIV known for his long sermons. The ladies began to bring chamber pots to church so they wouldn’t miss a single word.

François Boucher (1703-1770), La Toilette intime (Une Femme qui pisse), 1760s

As you spend more time at home, consider the objects that surround you. Which ones are essential or particularly dear to you? What do they say about your lifestyle or the society in which you live?

Visit us to see these objects and more in our permanent collection galleries!

Sources

Goldgar, Anne. Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age. University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Pavord, Anna. Tulip: The Story of a Flower That Has Made Men Mad. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019, “Bread Plate.” Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/208192.

Godden, Geoffrey A. Minton Pottery & Porcelain of the First Period: 1793-1850. Barrie and Jenkins, London, 1968.

Schama, Simon. The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age. University of California Press, 1988.

Hooper-Hammersley. Rosamond. The Hunt after Jeanne-Antoinette de Pompadour: Patronage, Politics, Art, and the French Enlightenment. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2011.

Jones, Christine A. Shapely Bodies: The Image of Porcelain in Eighteenth-Century France. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2013.

Sassoon, Adrian. Vincennes and Sevres Porcelain: Catalogue of the Collections. Malibu, CA: The Paul Getty Museum, 1991.

Jordan, Jennifer A. Edible Memory: The Lure of Heirloom Tomatoes and Other Forgotten Foods. University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Rubel, William. “But, Did the English Ate Their Vegetables? A Look at English Kitchen Gardens, and the Vegetable Cookery they imply (1650-1800).” Vegetables: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2008, edited by Susan R. Friedland, Prospect Books, 2009