On Being “Difficult”: Performing Criticality as an Art Critic of Colour

As the American-born builder of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), Sir William Van Horne’s aggressive methods of expansion can be linked to a capitalist desire that fed into the growth of his collection. While a transcontinental railroad represented progress in the late-19th century, it came at a cost. The expansion took place on Blackfoot (now Siksika Nation) territory that displaced the Indigenous population. Between 1881 and 1884, 17,000 Chinese labourers came to British Columbia to build the railway; these workers were paid $1 per day (less than their white counterparts), and given the most dangerous work, which resulted in many deaths. While the exact number of Chinese men who died building the railway is unknown, the Chinese Railroad Workers Memorial in Toronto estimates that more than 4,000 men died.

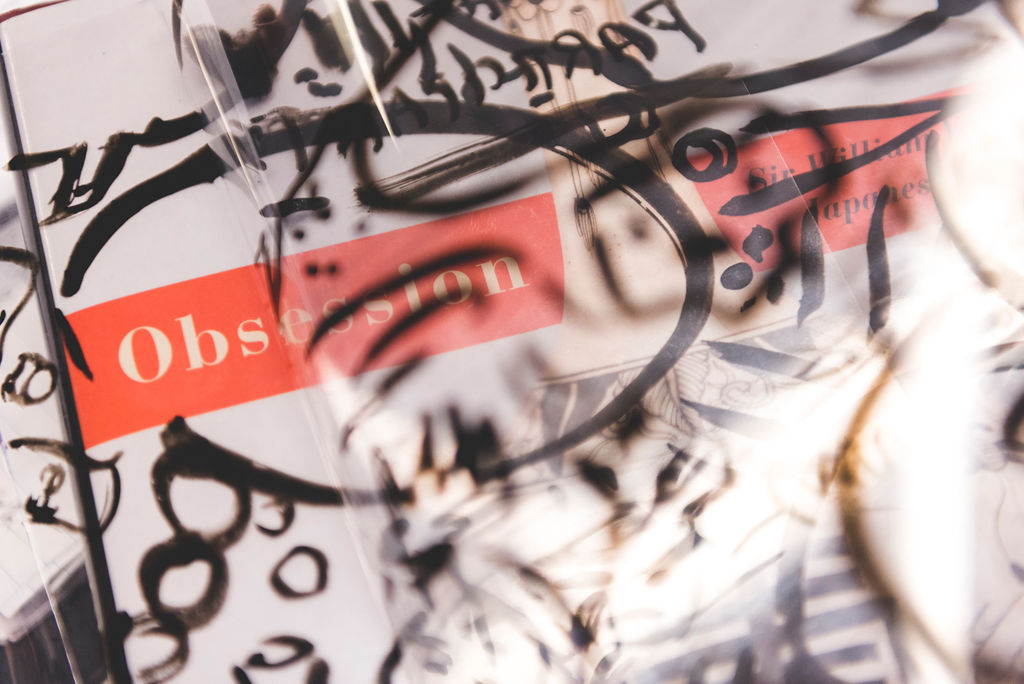

Artist Amy Wong was invited to explore the peripheralization of these histories within the exhibition Obsession: Sir William Van Horne’s Japanese Ceramics organized by co-curators Ron Graham and Akiko Takesue. Co-led by artist Amy Lam, a teach-in held in November unpacked the contemporary demand for QBIPOC (Queer, Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) arts labour.

Writer Merray Gerges and photographer Sarah Bodri were commissioned to observe the session. In the below text, Gerges reflects on the teach-in and her own emotional and intellectual labour as an art critic alongside a selection of photographs taken by Bodri during the workshop.

In undergrad at NSCAD, my nickname was “crit bitch.” This was partly because I co-founded and co-edited CRIT, an arts criticism publication, and partly because I was often the only person in studio critiques who would ever say anything actually critical.

Now that I am a critic by profession, “crit bitch” is no longer my nickname. But the implications of that reputation still follow me. If I attend a lecture or an artist’s talk and don’t ask any questions during the Q&A, acquaintances in the audience will take me aside later and grill me. What was my critique? And why did I hold it back? More often than not, these acquaintances are white. I almost always think this, but never say to them: There’s probably less at stake for you. Why didn’t you voice your critique for yourself?

It doesn’t occur to them that performing criticality for BIPOC, especially when it involves publicly critiquing institutions and their hegemonies, is a risky enterprise that tends to have serious consequences for our reputations and for our careers. We’re branded as “difficult,” as ungrateful troublemakers—even when the criticism is warranted. We’re positioned in a double bind: expected to perform criticality, but likely penalized when we deliver it. The art world expects—demands, even—this emotional and intellectual labour from some of its most precariously positioned individuals, whose inclusion is the most conditional.

It’s hard not to feel like performing criticality—especially when it’s inconvenient, when it points out a problem that requires systemic problem-solving, rather than Band-Aids—makes you disposable, or at the very least, undesirable. The anecdotes I could use to back this up empirically are too many, but the proof is partially in the numbers. A 2017 examination of the diversity of gallery management, conducted by Michael Maranda for Canadian Art, revealed, unsurprisingly, that gallery staff in decision-making positions are predominantly white. If we operate in an industry that proclaims to be conducive to diversity, yet diverse staff tend to be in entry-level or transient positions, could BIPOC ever feel like the institution is a safe space for their critique? Or that their critique of the institution is actionable? And what does it look like when art institutions encourage the emotional and intellectual labour of workers whom the art world treats like cannon fodder—only to make itself seem self-reflexive, responsive and open to critique?

Within the first weeks after Obsession‘s opening at the Gardiner, a portion of its public programming addressed what the exhibition’s curatorial contextualization didn’t do much to address. Van Horne’s enterprise, the Canadian Pacific Railway, was built on the backs of the de-facto slave labour of Indigenous and Chinese migrant workers, on stolen Indigenous land, and because the exhibition evades this colonialist legacy, its uncritical display of his taxonomic collection of Japanese ceramics could be read to glorify his orientalist collecting impulses.

The programming, which was organized a year ago, began to dissect how an exhibition that was arranged three years ago lands today—at a time when, for better or for worse, the term “reconciliation” is on many lips. During the Power and Possession panel, Sean O’Neill (host of CBC’s In The Making) facilitated a discussion on the ethics of collecting and displaying problematic historical material, in light of contemporary discourses regarding cultural appropriation and increasingly common repatriation efforts. The panelists were Candice Hopkins, a prominent Indigenous scholar and curator; Adrian Stimson, a celebrated Indigenous artist; and Mark Engstrom, the ROM’s Deputy Director of Collections & Research.

In the Q&A portion, artists Amy Wong and Amy Lam, both of whom were slated to facilitate further critical programming a few days later, asked: what’s the point of a panel now? Can it be anything more than an afterthought at this stage? Could it perform anything beyond the public optics of damage control? Is there space for the institution to learn from its missteps?

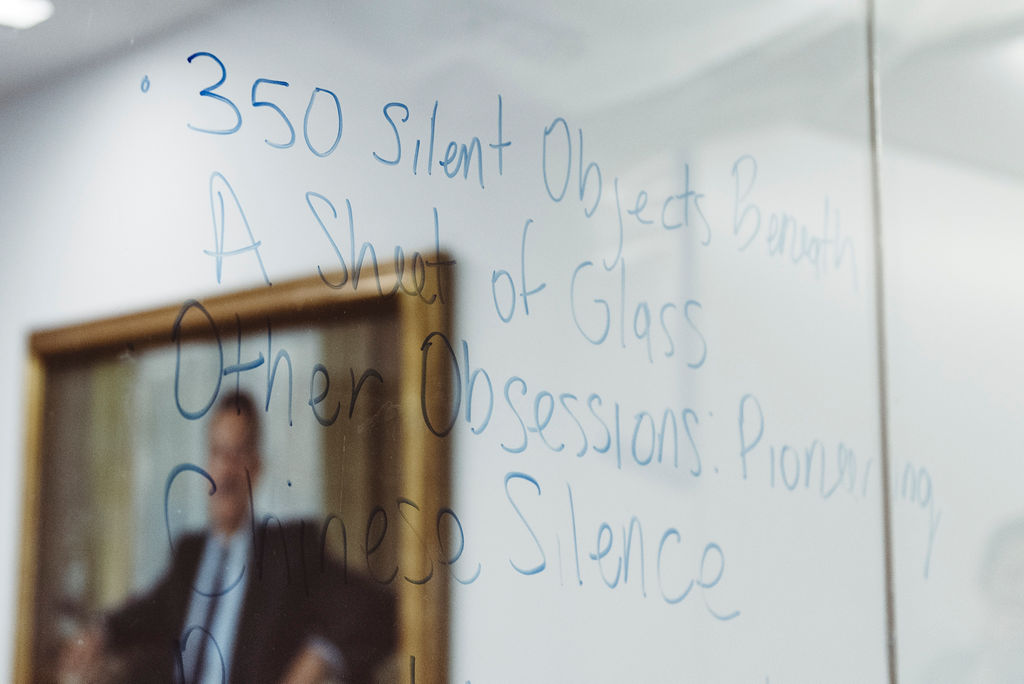

We teased these questions apart a few days later in Wong and Lam’s Institutional Critique Teach-In, which generated the content for two editions of a book jacket covering the Obsession catalogue that visitors can see and take from the exhibition. They pointed out how BIPOC are enlisted to perform critique of an exhibition through its public programming—which is community-oriented, small-scale, free of charge, ephemeral, and not constantly publicly visible like the exhibition space is.

“As a BIPOC person in the arts, the default is to be in a state of institutional critique – even if that’s not part of your practice,” Wong began. “We’re bitter about it, but if we don’t do it, who will?”

The workshop took place on a Sunday afternoon in a meeting room at the Gardiner’s staff offices. To provide the context that the exhibition omits, Lam shared with us her research on the hardships of the railway workers, and made space for a group reading of a harrowing fictionalized account of a day in the life of Chinese migrant worker from Maxine Hong Kingston’s China Men. She fact-checked the didactic panels, which downplay the number of deaths and minimized that many of them were Chinese. The premise of the collection and the framing of the exhibition are dated, but why didn’t the didactics fully address the narrative that the objects on display could never convey? The role of public programming is to support an exhibition by enhancing and expanding how the public might engage with it—not to make up for the exhibition’s omission of a crucial perspective.

If we don’t have a voice at the table then we don’t have power to make decisions, Hopkins stated at the panel, and participants in the workshop, myself included, added: when we are given a voice at the table, which table is it? If the labour of institutional critique tends to fall on BIPOC who are likely not in decision-making positions, and if it happens retroactively, how much of a difference could the critique really make?

That question is complicated for me: as a critic, and first editorial staff person of colour at Canadian Art. In many ways I now reap the rewards—in cultural capital and in capital capital—of “crit bitch,” but in many ways, performing institutional critique, internally and externally, has taken a steep toll, as it has and does for many BIPOC occupying institutional positions. The burden of this labour overtaxes us in the present, and in the long run ensures that many BIPOC cultural workers won’t last long enough to become decision-makers.

If the art world wants to move beyond lip service in practices of equity, BIPOC must be hired for consultation, pre-emptively, and not for atonement, retroactively. In the future, I’d like to see the conversations put forth by the critical programming I’ve described—the panel, the teach-in, this piece—happen before the exhibition. And I’d like to see these conversations carried out by more than just the BIPOC in the room.

Join us from 1- 4pm on Saturday, January 12 for the Teach-In Edition Launch.

Merray Gerges is a Toronto-based critic, editor and investigative journalist. She studied journalism at King’s University and art history at NSCAD, where she co-founded and co-edited CRIT, NSCAD’s first student newspaper. In summer 2016, she was Editorial Resident at Canadian Art, where she is now Assistant Editor. Her reporting and criticism have appeared in Canadian Art, C Magazine, MOMUS, the Walker Art Center Reader, Hyperallergic and more, discussing topics ranging from the radical potential (and shortcomings) of intersectional feminist memes and art selfies, to art-world race politics.

Sarah Bodri is a photo-based artist living in Toronto and received an Honors BA from York University in French Language and Literature & Gender studies. Bodri’s self-taught practice hinges on analogue photography and treats portraiture as a potential means of empowerment. By employing deep empathy and vulnerability while working, and more recently using experimental photo techniques to produce ‘participatory portraits’, she aims to transcend the power dynamics implicit in lens-based photo work. Her practice explores boundary establishment / dissolution, artistic labour, affect and the environment.