Five objects with curator Akiko Takesue

Sir William Van Horne was an exemplary collector from an early age, gathering and cataloguing fossils he found by his family’s home in Joliet, Illinois as a young boy. After he made his fortune overseeing the development of the Canadian Pacific Railway, Van Horne turned this knack for collecting towards art, joining many other business leaders who had also cemented their wealth during this period of colonial expansion in accumulating large amounts of European and Asian art.

Though perhaps best known for his collection of European paintings—the largest in Canada—Van Horne dedicated space in his private study to his true passion: Japanese ceramics.

Fascinated by the tactility of clay, domestic wares were Van Horne’s ceramics of choice, as he deemed objects with utilitarian function more ‘authentic’ than ones made for export to the West. Indeed, Van Horne’s love for Japanese ceramics wasn’t rooted in their aesthetic value, but rather in researching, identifying, and classifying the regional kilns, types, techniques, and marks of the objects by means of observation and touch.

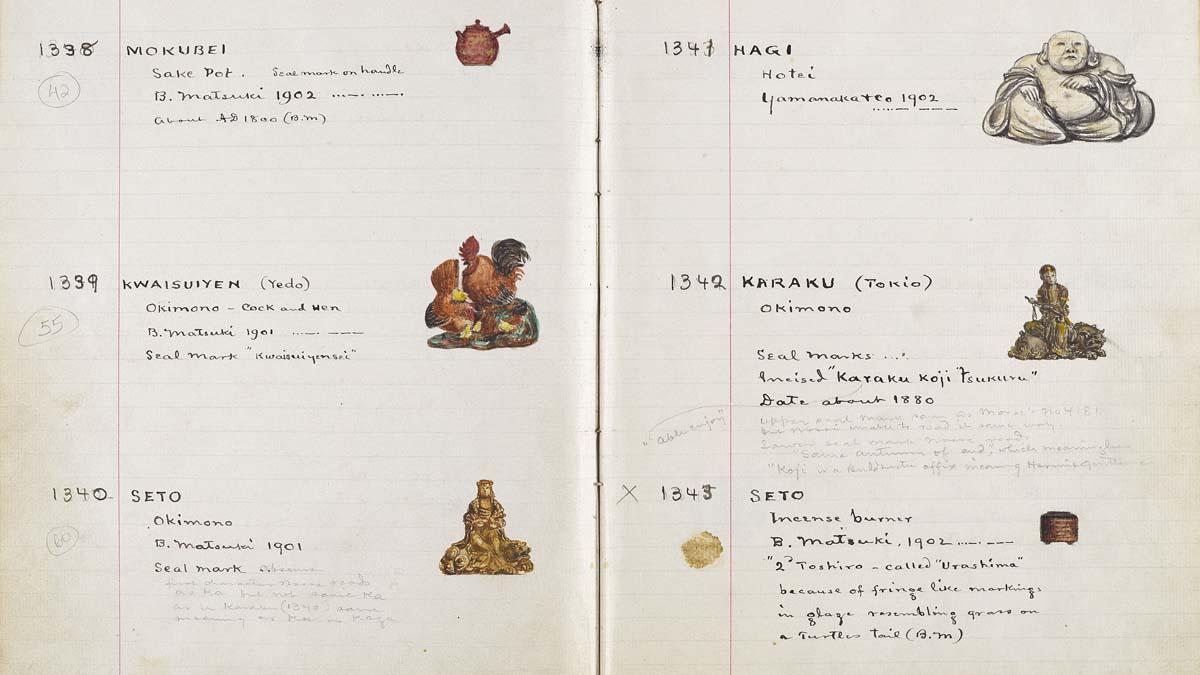

The prolific collector eventually accumulated 1,200 pieces from 1893 to 1903, meticulously cataloguing each one in his notebooks, and painting watercolours of those he loved most. According to his contemporaries, Van Horne was eventually able to identify pieces while blindfolded through touch alone.

Today, just over 400 pieces from Van Horne’s collection remain. Obsession: Sir William Van Horne’s Japanese Ceramics brings together 347 pieces from the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the Royal Ontario Museum, complemented by Van Horne’s exacting watercolors, elaborately annotated notebooks, letters, and archival material, much of which comes from the Art Gallery of Ontario.

To learn more about some of the objects on display and to get a glimpse into the mind of the collector, we asked Dr. Akiko Takesue, assistant curator of the exhibition, to pick five of her favourite objects from the exhibition:

It is a very difficult task for me to choose only five objects from Sir William Van Horne’s Japanese ceramics collection, as I have done close research on every single object of over 400 pieces that survive today. I have a special memory, big or small, of each of them.

But if I had to select five, I would say that the rounded square tea bowl with flowing glaze by Nonomura Ninsei is the most memorable piece to me. I witnessed first-hand the shift in its attribution—from a mere “copy” of Ninsei work to an authentic Ninsei piece. The discovery—or more precisely, re-discovery—of the authenticity of this piece became the focal point of my research and determined its direction. But first and foremost, the beauty of this piece originally drew my attention. Its elegant and delicate form, calm and warm earth colour, and thin yet multi-layered glaze all attest to the reputation and popularity of this 17th-century master potter. And as with every good tea bowl, its true beauty is revealed when it’s held in your hands—the shape, weight, and texture all perfectly appreciated.

I tend to be attracted to earlier pieces—those made before the 18th century. The Ko-Imari style ovoid jar with birds and turtle and Early Imari style sake bottle in tea-whisk shape are my favourites. Both are from the mid-17th century, and early productions of the Imari style. The shape of the former is somewhat distorted and the painted decoration is simple and rough. The latter is covered with cracks that were not supposed to appear, with a large “bellybutton” or blemish on its lower body. These elements might be considered flaws from the viewpoint in which perfection equals beauty. To some Japanese eyes, however, these “blemishes” appear appealing instead: a sense of beauty highly affected by the so-called wabi-sabi aesthetic, which cherishes simplicity, roughness, and imperfection.

The next piece also reflects this aesthetic: The Gohon type tea bowl made in Busan, Korea in the second half of the 17th century. The prototype of this type of bowl was said to be a Korean rice bowl, but Japanese tea practitioners at the time found beauty in these simple, rough bowls and used them in tea ceremonies. Its form can hardly be called perfect; the glaze was whimsically applied, and even retains a trace of the potter’s thumb. But such imperfection creates a sense of intimacy and beauty, a sense that I too share with the tea masters of 400 years ago.

The fifth piece I chose is the Satsuma ware serving bowl with a rippled rim, mainly because of its peculiarly textured glaze—called “snake skin” glaze. This effect is achieved by applying multiple glazes at the same time. Together with its stubby form—low walls with a wide mouth shaped like a stylized flower—this bowl has a striking presence among others. The kin-tusgi or gold-lacquer repair on the mouth attests the importance of this piece for the previous owners.

These picks are truly my personal view. Some of my friends have told me their favourites, completely different from mine, which I was very happy to hear about. That is what the Van Horne collection is about—not about masterpieces but about the specific relationship between the objects and the collector or viewer.

Akiko Takesue is exhibition research assistant at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and is currently working on a Japanese art exhibition to open in 2019. She completed a PhD dissertation on the Van Horne collection of Japanese ceramics in 2016.

Obsession: Sir William Van Horne’s Japanese Ceramics is currently on view at the Gardiner Museum until January 20, 2019.

Images: [1] Obsession: Sir William Van Horne’s Japanese Ceramics (installation view), 2018. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid [2] William Van Horne, Catalogue “C.B.,” ca 1876, E.P. Taylor Library and Archives, Gift of the Estate of Matthew S. Hannon, in memory of Mrs Willam Van Horne, 2001, LA.VHF.S3.12. Image © Art Gallery of Ontario. [3] Obsession: Sir William Van Horne’s Japanese Ceramics (installation view), 2018. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid [4] Nonomura Ninsei, Rounded square tea bowl with flowing glaze, Kyoto | Edo period, mid 17c., Royal Ontario Museum 944.16.24 [5] Ovoid jar with design of birds and turtle, Arita ware, Ko-Imari style, Saga | Edo period, mid 17c., Royal Ontario Museum 909.22.2, Gift of Sir William Van Horne [6] Sake bottle in tea-whisk shape, Arita ware, early Imari style, Saga | Edo period, Royal Ontario Museum 909.22.18, Gift of Sir William Van Horne [7] Hemispherical tea bowl with irregularly shaped mouth, Busan ware, Gohon type, Korea | Choson dynasty, mid 17c., Royal Ontario Museum 909.22.72, Gift of Sir William Van Horne [8] Square sake bottle with landscape design, Kyoto ware, Kyoto | Edo period, second half of 18c., Montreal Museum of Fine Arts 1944.Dp.27, Adaline Van Horne Bequest